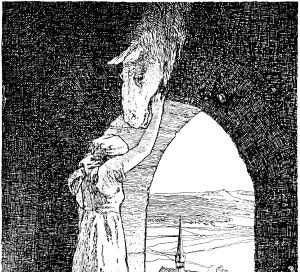

Blood-dripping keys and rose-scratched eyes. Some thoughts on death, mutilation and the gruesome in fairy tales.

What happens when we censor fairy tales? What happens when we don't?

The other day, I was looking for an English translation of one of my favourite fairy tales growing up, Allerleirauh. To make a long journey as short as possible: it took me a long time to find a volume that had the tale at all and to my great disappointment, it was censored.

Allerleirauh is a Princess who, at the beginning of the tale, doesn’t have a name just yet. With her golden hair, she resembles her mother so much that the grieving king, her father, desires to marry her after the Queen’s death. Despite his advisors’ shock and his daughter’s horror, he sticks to his decision and plans to enforce his will. The Princess flees, disguising herself using a coat made from the fur of every kind of animal that lives in her father’s kingdom (in turn earning her name, All-kinds-of-furs).

The English version I found has her father insisting that she marries one of his advisors who will then rule after the king’s death. The disgust and horror everyone involved feels at this suggestion feels ridiculous, frankly, when compared to the original plot. The threat of incest gets turned into a question of marriage within the appropriate social class.

Any trance of discomfort being ironed out of fairy tales (and the story being flattened in the process) is nothing new. From the twelve dancing princesses being reunited with their princes to Disney’s Arielle getting her voice back, many fairy tales are distorted into Hollywood Happy Ends.

But apart from frog princes being kissed instead of being thrown against walls or random by-chance meetings written in to make sure no complete strangers are kissing dead young girls, there are many instances where more graphic moments are edited out of certain tales. In The Seven Ravens, another favourite of mine growing up, a young girl has to find the glass mountain at the end of the world to save her brothers. She loses the key to the mountain — a little bone — and, desperate, finally uses her finger to open the gate. In a picture book I paged through the other day, she simply sticks her finger into the keyhole and turns it. But we of course know that’s not how the tale goes. We know that she cut off her finger to use as a substitute. Bone for bone, blood smeared on glass.

And of course this is very gruesome (I remember how much this part moved me as a child), but she gets her finger back (with spit or magic, I forgot which). It’s the same as Tsarevitch Ivan, whose Grimm-brother is pushed down a well by his jealous brothers, while Ivan is cut into pieces first. Depending on the tale, a wolf or fox will come and safe him , because — and that’s what’s so important to me — life and death and the body are strange things in fairy tales.

“How long did I sleep for, Grey Wolf?” – “You would have slept forever,” replied Grey Wolf, “if I had not saved you.”

(Tsarevitch Ivan, the Firebird and the Grey Wolf)

Fairy tales are full of mysterious rituals, there are webs of sevens and threes to get lost in and meals to be shared with animals or strange creatures in the woods. People are told over and over to pick the worse of two options and repeatedly get punished for picking golden saddles, golden doors or golden cages. Those rules feel like steps to endless, ever-same and ever-changing dances, and they extend to the bodies of the protagonists.

The body in the fairy tale is a curious entity, frequently mutilated and restored back to health. Think of Iron Henry, whose agony at his prince being turned into a frog was so great that he feared his heart would break, so he had three iron rings put around it to hold it together. Or, again, think of the sister of the ravens and her finger-key — or her sister in spirit, the sister of the swans, who spends six years weaving stinging nettle shirts with her bare hands. Despair is expressed through physical pain the characters oftentimes inflict upon themselves. To what limits are we willing to go in moments of desperation? In fairy tales, the protagonists oftentimes take a very physical approach to the self-sacrifice.

Mutilation is one step, death the next. There are the gruesome punishments the wicked villains suffer through, of course: coal-glowing shoes and barrels covered in nails. But death in fairy tales isn’t reserved for the evil. Animals or humans are often killed and cut up — either to be brought back later or to reveal their true selves. Death isn’t final, it can be an in-between state or a new beginning. From Ivan’s friend the wolf to Falada, from Snow White to the sister whose brother turned into a deer, death happens and doesn’t happen.

What is the use of those gruesome, confusing details? What happens if they’re cut out?

For one, the tale collapses. Allerleirauh running away because she doesn’t want to marry an advisor does her a disservice by making her look like a stuck-up, blue-blooded monarchist. The Disney version of Sleeping Beauty already knowing her prince (so she isn’t kissed by a stranger, shocking the USAmerican youth) causes many hand-wavy problems when it comes to her hundred-year slumber. [A secret note: I very fondly remember a German adaption from 2014 or so, where the hundred year difference was addressed and the Prince lived during Voltaire’s times, an enlightened monarch who tried to sail into the castle with a hot-air balloon, but couldn’t, in the end, escape the rules of the tale, stomping in alone with a century-old sword he barely knew how to wield. It was so fun! But back to bloodshed:]

Death and pain are just as ever-present in fairy tales as love and magic are. All aspects are exaggerated, and fantastical beauty and fantastical pain go hand in hand. Erasing every last drop of blood and the lingering threat of incest disturbs that equilibrium. It feels a little dishonest to pretend that only good things happen. Only the bad ones die, and we watch their suffering with glee (coal and nails). Even further: It gives the bad things much more power than they had in the original tale. The prince who fell from Rapunzel’s tower is blinded by the rose bushes, but her tears heal him. Denying him his mutilation is not only denying him his blindness, but also the magical cure. Denying Ivan his death is denying him his resurrection. The magic is lessened in its power. After all, in a real fairy tale, anything can happen. Even this.

Apart from that, the loss of the grotesque robs the tale of the questions it prompts us to ask about our own body, our own morals, our own mortality. What does it mean to cut off a finger? What does it mean to lose a friend, a brother? What does it mean to wander the world alone, blind, lost? We feel empathy for the hurt, we understand what drives the ones who hurt themselves.

Besides, again: fairy tales are woven through with secret, repetitious rituals. The reading process, the process of telling and re-telling those tales are part of that. Just as the heroes will choose the golden saddle, the golden cage and the golden door, over and over again, three times in a row, the little mermaid will dissolve into foam and Falada will be beheaded. Over and over, without fail, they will die - until we come together again and tell the story once more.

Let’s remember how German fairy tales end: And if they haven’t died, they’re still alive today.

Oh this is such an interesting take! I love fairytails and their gruesome nature, it's sad to see them become more and more watered down </3